One way to think of a business is as an interconnected system that turns investments — labor, time, money, raw materials, equipment, etc. — into profit.

So if you were to open a lemonade stand, you’d invest in the stand, invest in the lemons, invest in the sugar, and turn that into profit by selling cups of lemonade at a high enough margin.

But what if instead of just selling lemonade, you could also sell lemonade-making-as-a-service?

You’ve already built the infrastructure to produce lemonade, and instead of just earning money from end customers who buy lemonade, you could also profit from businesses that sell lemonade — all thanks to your new LMaaS offering.

That’s smart business. Or at least it could be.

That’s a simplified example of course, but that playbook — turning costs centers and infrastructure investments into new revenue streams — is used by some of the savviest companies around the world.

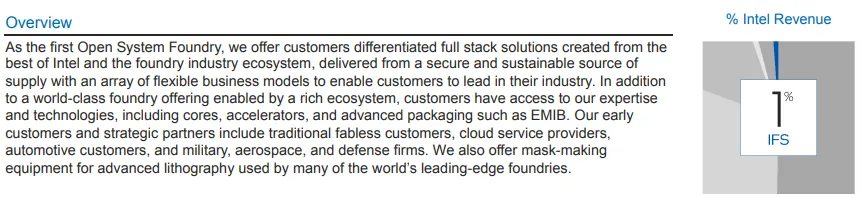

A recent example is Intel.

In his first public announcement since becoming CEO in 2021, Intel’s chief executive Pat Gelsinger announced a strategy shift.

The company, which has built significant manufacturing expertise and infrastructure over its 50+ years of operations, will no longer just make its own lemonade semiconductors, it will also provide lemonade-making chip-making-as-a-service under a new ‘open systems foundry’ model.

In other words, Intel is transforming one of its main cost centers — chip manufacturing — into a new revenue stream.

And while the Intel Foundry Services business unit contributes just 1% of Intel’s revenue today, the company sees this model as key to its future. Gelsinger said in 2021, “We conservatively size the foundry opportunity as a $100 billion addressable market by 2025.”

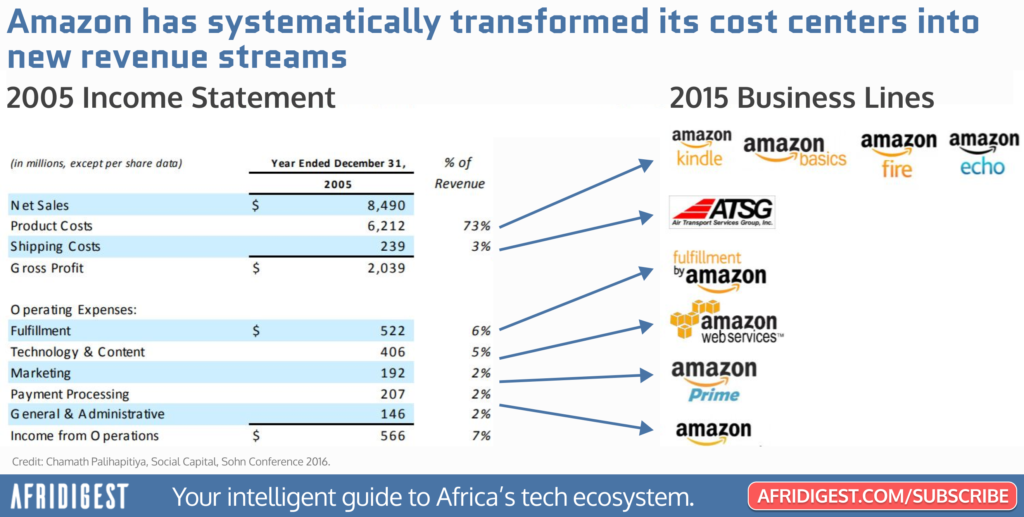

While the impact of Intel’s transformation remains to be seen, one company has famously reaped massive benefits from running this costs-to-revenues playbook: Amazon.

The company has systematically transformed all of its main cost centers into long-term sources of revenue in one form or another.

Perhaps most famously, it transformed its tech infrastructure — a significant cost center for large e-commerce players — into Amazon Web Services (AWS), the B2B cloud computing platform with over 1 million active users that now generates over $80 billion in revenue annually and accounts for ~75% of the company’s operating profit.

But that wasn’t always the plan.

As the company set out to help large retailers build Amazon-powered online stores in the early 2000s, it realized its internal systems were poorly designed for this and it needed to address its technical debt.

So the company began working on a centralized, API-driven platform as a means to optimize its tech operations. And from then on, Amazon’s engineering teams were expected to build in an API-first fashion, paving the way for today’s AWS offering.

As Jeff Bezos explains in the following 2008 video, “We realized as we started architecting this set of APIs that it would be useful for everybody, not just for us, so we said, ‘Look, let’s make it a new business. It has the potential one day to be a meaningful business for the company and we need to do it for ourselves anyway.’”

Across Africa, a number of companies are following that playbook: identifying a cost center they’re already paying for or an area of significant investment, and turning that into a business that serves external clients.

Here’s a look at three of them.

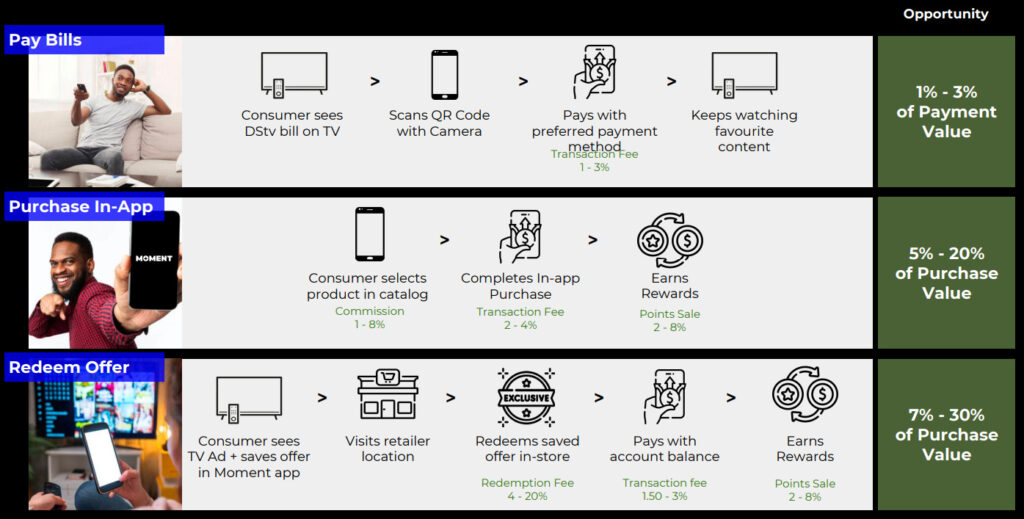

Transforming processing fees into payment revenues: MultiChoice

South African video entertainment platform MultiChoice Group, one of Africa’s top fifty companies by market cap, takes in $3.5 billion in payments across 40+ countries every year.

And, according to CEO Calvo Mawela, it pays $60 million in commissions to various payment processors for the pleasure of doing so.

So the company is launching a pan-African payments platform called Moment in partnership with Israeli fintech-as-a-service unicorn Rapyd and US VC firm General Catalyst.

MultiChoice has invested $3 million in Moment so far, and while the CEO notes that “fintech is a highly competitive space,” he believes that “Moment will enjoy significant competitive advantages at launch” — such as being able to leverage existing integrations with 200+ payment partners across Africa.

Moment’s vision isn’t just to power its own payments, but to tap into fast-growing revenue pools across the continent — in SME payments, pan-African e-commerce, trade between Africa, and more.

Here are some potential opportunities MultiChoice is mulling, for example:

Transforming compliance costs into identity verification revenues: Chipper Cash

Pan-African fintech Chipper Cash has about 5 million registered customers today across Ghana, Uganda, Nigeria, Tanzania, Rwanda, South Africa, Kenya, and a few developed markets.

And it’s had to pay identity verification providers a hefty sum to perform digital KYC on those customers for compliance purposes — and their offerings didn’t meet Chipper’s needs entirely.

So the company spent 18 months building an in-house solution to plug those gaps.

And it recently launched a Chipper ID product suite that’s open to all businesses needing digital KYC solutions across Africa.

Here’s how Chipper Cash’s CEO Ham Serunjogi described this to me:

Transforming payments infrastructure costs into API revenues: Paga

Nigerian mobile payment platform Paga is among the pioneers in the space.

The fourteen-year-old company spent a lot of resources on building reliable payments infrastructure in Nigeria in its early days.

And after realizing the strong need in the market, Paga built a set of APIs which it opened up to developers in 2021 — in a move inspired by AWS.

Here’s how Paga’s CEO Tayo Oviosu described this to me:

Final Thoughts

Oviosu’s point above about having to build infrastructure that didn’t previously exist in a common one.

And while Chipper Cash’s situation was a bit different — ID verification infrastructure already existed — the company still had to build out a custom solution for its specific needs.

And that’s one hallmark of many companies operating in Africa today: they often have to build their own infrastructure to scale.

That’s one reason building venture-scale startups on the continent generally costs more than elsewhere initially, but over time these companies tend to enjoy leverage in the form of lower staff & overhead costs.

And in addition to that, as the playbook above shows, there are often significant opportunities to turn infrastructure investments (and ongoing costs) into additional income.

Share: